Using generative models, well, to generate data

- One underappreciated use case of generative models is effectively creating realistic tabular datasets

that preserve the underlying statistical properties of the original data.

- Leading libraries for data synthesis include Synthetic Data Vault, YData-Synthetic, and Synthcity.

- Practical applications include navigating the bottlenecks of sharing sensitive data with vendors or augmenting datasets for rare events, such as product recalls.

- Ultimately, this approach enables a data-centric workflow even when data is scarce or biased, ensuring models are trained on a high-fidelity representation of reality.

Podcast-style summary by NotebookLM

Introduction

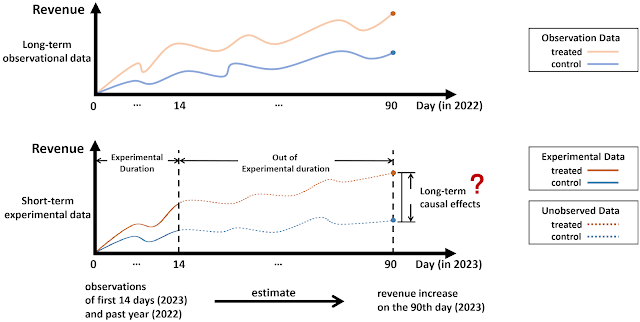

How can we use generative models beyond large language models in data science solutions? We recently discussed this question. Around the same time, I needed a dataset for a chapter of the Causal Book and ended up using a generative model – its unreasonable effectiveness in executing the task motivated this post.

Our objective is twofold: (1) use the example in the book to highlight the libraries for generating tabular data, and (2) discuss the implications for data science projects and data centricity.

Academic's take

The background story

In seeking a suitable dataset for the regression discontinuity chapter of the Causal Book, I decided to use data from an Online Travel Agency (OTA) where customers advance to a higher loyalty tier based on their past spending. However, this type of data is proprietary, and I couldn't publish it. Then an idea occurred to me: what if I had a small sample of data (say, 100 or 1,000 observations) from an OTA like Expedia? Could I realistically scale it into a reasonably large dataset for the chapter? The answer was a plausible yes, given how well machine learning models perform in pattern recognition and replication – but did I need to code a synthesizer from scratch? Fortunately, no.

Meet "Synthetic Data Vault"

Synthetic Data Vault (SDV) uses a recursive algorithm to create a generative model of a relational database. First, it maps the relationships between tables, creating "extended tables" by aggregating statistics from child tables into their respective parent tables. Next, it uses a multivariate Gaussian Copula to model the correlations between columns (both original and aggregated) within each extended table. Finally, the algorithm synthesizes new data by sampling from these learned models, starting with the parent tables and recursively generating corresponding child table rows.

Back to the task: Creating realistic OTA data

In practice, we chose not to use real data as a seed to avoid potential issues with usage rights, as the legal implications of using generative models are not yet clear. Instead, we engineered a realistic seed dataset for a customer loyalty program at a major Online Travel Agency. We defined the dataset's functional form with high-fidelity attributes (e.g., age, number of bookings, and average booking value). We also embedded the causal effect we needed: "the effect of receiving Platinum Status on a customer's future spending." You can see the book chapter for details.1

For now, let's assume this is our "real" dataset. To evaluate how well SDV's Gaussian Copula synthesizer maintains statistical properties while introducing some randomness to simulate realistic variation, we split the data into training and testing sets to benchmark the results.2 The process involved two steps:

1. Creating the seed data: We sampled from our "ground truth" dataset (1,000 observations). In reality, this would be a real dataset, from a new or niche market, or a new product launch. The Director discusses these potential use cases in more detail below.

2. Scaling the seed data: To scale the dataset while preserving the existing joint distributions, we trained a Gaussian Copula Synthesizer on the seed dataset and generated 50,000 observations. This process required specific adjustments for our use case. To ensure the generative model did not smooth out the sharp discontinuity we needed, we used a residual-based reconstruction method that involved independently and deterministically recalculating the treatment status post-generation. See the Regression Discontinuity chapter of the Causal Book for those details.

Unreasonably effective results

The histograms shown at the opening demonstrate how closely the synthetic data distributions match the "real" data. Histograms and descriptive statistics for the outcome variable are also provided above. Clearly, correctly modeling the relationships among variables is much more critical than scaling a single variable. For a more complete picture, including covariate balance statistics for both datasets, please refer to the book chapter.

The regression discontinuity plot is below. This plot uses binning to simplify an otherwise messy chart containing 50,000 individual customers. Most importantly, the causal effect measured at the cutoff matches in both datasets.

Now what?

Our starting inspiration was that this use case of generative models is applicable to other settings and is potentially very useful for data science teams solving business problems.3 I will leave the discussion of these broader applications to the Director and conclude my part by summarizing three libraries I discovered during this journey:

| Synthetic Data Vault | YData-Synthetic | Synthcity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best for... | Data Scientists & Enterprise. Relational databases with multiple tables. | Data Scientists. Time-series data & quick profiling via UI. | Researchers. Benchmarking new algorithms & privacy tech. |

| Ease of Use | High (Plug-and-play, excellent docs) | Medium (Includes a Streamlit UI helper) | Low (Complex API, steep learning curve) |

| License | Business Source License (Free for research only) | Apache 2.0 (Open Source) | Apache 2.0 (Open Source) |

| Handling Missing Data | Automatic (Handles standard nulls out of the box) | Manual (Requires preprocessing) | Manual (Requires imputation) |

| Privacy Features | Basic Anonymization & Constraints | Standard Privacy-preserving GANs | Advanced. Differential Privacy & Fairness metrics |

| Under the Hood | Statistical (Copulas) & Deep Learning (CTGAN) | Deep Learning specialized for Time-Series | Massive library of experimental models (Diffusion, GANs) |

Basically, Synthetic Data Vault (SDV) differs from the other two in its focus on relational stability across multi-table databases, offering high usability through comprehensive documentation and automated handling of missing data via a transformer-based solution (RDT - Reversible Data Transforms). In contrast, YData-Synthetic prioritizes time-series and sequential data generation (particularly for financial applications) by leveraging algorithms like TimeGAN, though it often requires more extensive data preprocessing. Finally, Synthcity serves as a research-focused framework for benchmarking state-of-the-art algorithms, including diffusion models and adversarial autoencoders. While it integrates advanced features such as differential privacy, it presents a steeper learning curve.

Director's cut

In what cases would a data science team working with real data need to generate and use synthetic data? We use synthetic controls in our models, so how else can we benefit from generative models in creating realistic datasets? Here is my take:

Data sensitivity as a barrier to collaboration: In almost every data science team I have managed, we collaborated with outside vendors. These partners provide software support (e.g., Gurobi for optimization) and often ask for our data to tune the services they provide (e.g., optimization run times). In other cases, a vendor may offer a competing solution to one we built in-house. While we may be open to outsourcing, we need to benchmark our internal solutions against external ones using the same data to decide whether to switch. These data-sharing challenges also extend to research collaborations.

The problem is that sharing our data invariably triggers legal and compliance reviews. These reviews are time-consuming, as teams must verify whether the data contains personally identifiable information, protected health information, or sensitive financial transactions. Instead of allowing data sharing to become a bottleneck, we are better off creating a statistical "twin" of the original dataset. Generating a synthetic version that preserves its statistical properties without compromising privacy offers immense value.

Underrepresentation of rare events: This is a common problem. We train our models on historical data, which often contains an insufficient number of rare events to build robust predictive power. Over the past five years, we have navigated COVID-19, catastrophic weather events, natural disasters, and significant tariff effects. The question remains: if historical data lacks the necessary sample size for these anomalies, or if rare events affect only localized markets, how can we augment our training data to ensure model resilience?

This is another use case where realistic synthetic data can be handy. In retail, for example, product recalls are rare, but when they occur, they cause significant disruption to store operations and supply chains. If an alternative product exists, demand shifts rapidly, further aggravating the impact on inventory. Because recalls are generally clustered in a handful of categories, historical data is often too sparse for robust model training.

Our solution is usually to generate synthetic data by first identifying products or categories with similar statistical profiles, which is a similarity matching problem. We then use the patterns from these similar product recalls to generate the synthetic (time-series) data required to train our models. While this use case may feel less critical than the sensitive data problem, it is frequent and extremely helpful for scenario planning when a rare event is looming.

Two other use cases arise when the available data is historically biased or critically limited. While I don't have experience with the former, the latter is another common challenge in retail: "cold start" problems. Think of a retailer launching a new store format, a private label brand, or a completely new category (such as plant-based meats) where no historical transaction data exists. In these scenarios, I can see how the synthetic data algorithms highlighted above provide significant value by bootstrapping our predictive models.

Our discussion here underlines the potential of generative models beyond the world of LLMs. As transformative as language models are, the business value of other generative models, such as those for tabular data generation, remains largely underexplored and untapped. We will continue this discussion with other topics.

Implications for data centricity

Data centricity, or staying true to the data, is not always possible or desirable, especially when the data is nonexistent, missing, or biased. Generative models enable the creation and scaling of realistic datasets to mitigate these problems. When starting with a real seed dataset that is then scaled while preserving its underlying statistical properties, generative models play a critical role in allowing a data science team to remain data-centric. In this discussion, we covered tools for creating realistic tabular datasets that remain consistent with reality, leading to more robust models built on correct assumptions and accurate insights rooted in the actual data. By using generative models to synthesize and scale high-fidelity data, we shift our focus from "fixing the model" to the properties of actual dataset. This allows us to maintain a data-centric workflow even in the face of data scarcity or bias, ensuring that the model is trained on a representation of reality that is reliable and verifiable.

Footnotes

[1] Details of the data generation process can be found in the Regression Discontinuity chapter of the Causal Book.↩

[2] In the book, we generated the dataset using a nonparametric approach: using a structural simulation followed by a multivariate Gaussian Copula synthesizer trained on residual errors to be able to keep the causal effect intact.↩

[3] It is worth noting that the use case we discuss here is distinct from the more well-known synthetic control methods.↩